There is an old saying that no posture is bad unless you get stuck in it. The problem is that people often do get stuck in bad postures. And this is especially true for the thoracic spine. A further problem is that postural distortion of the thoracic spine, even when advanced, is often asymptomatic and therefore ignored by the client, but can be a major cause of other postural distortion and pain patterns in the body. In this way, the thoracic spine could be viewed as a silent saboteur of our health. The client may not even mention the thoracic region when describing their problem, but we need to always consider and assess the thoracic spine when evaluating our client’s health.

Rounded Back

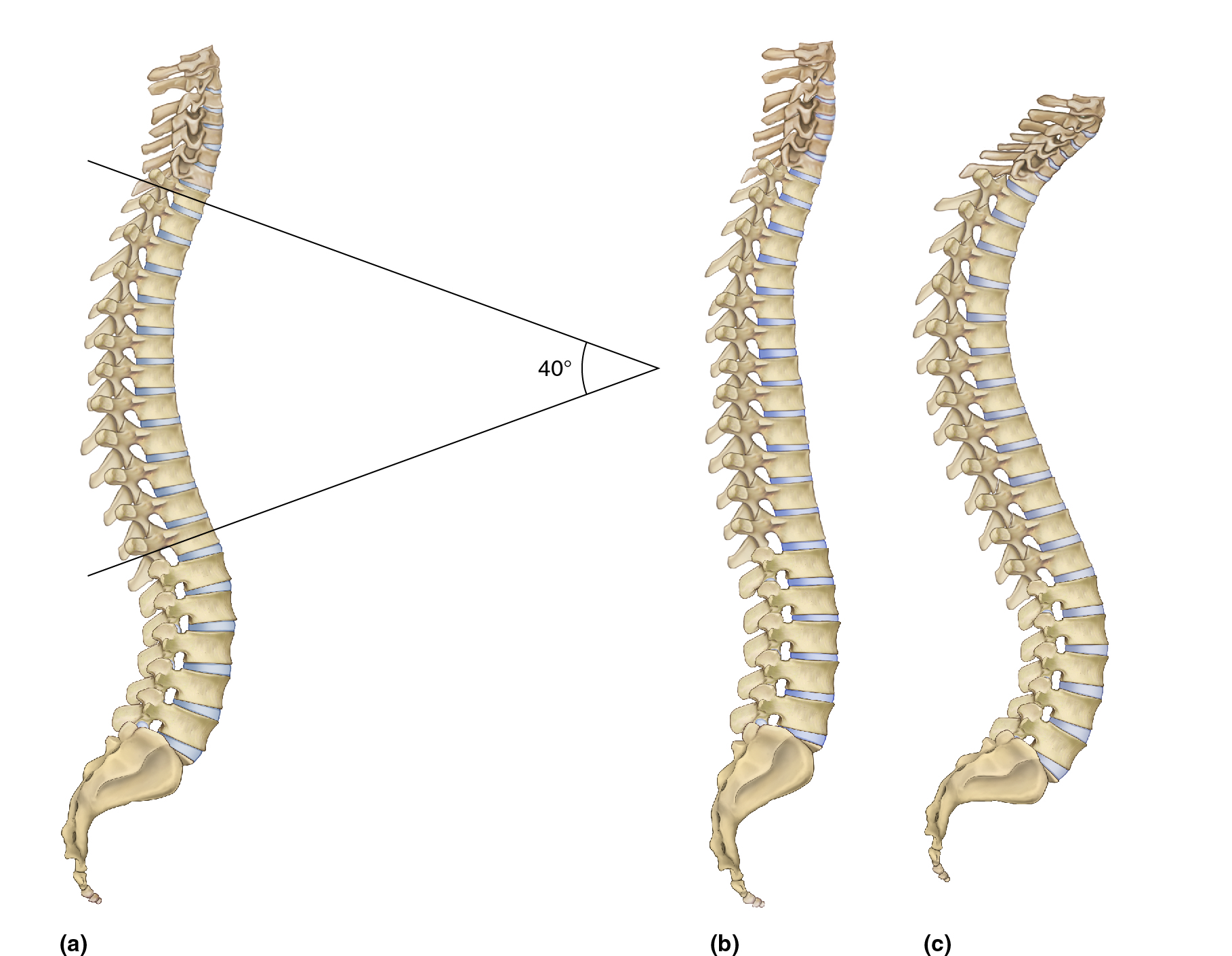

A healthy thoracic spine should have a natural kyphotic curve that measures approximately 40 degrees (Figure 1A). Although it is possible for this curve to be abnormally decreased, in other words, hypokyphotic (Figure 1B); by far the more common postural distortional pattern is for the thoracic spine to become hyperkyphotic (Figure 1C). In lay terms, this is often described as rounded back.

Figure 1. A, healthy natural kyphosis of the thoracic spine measures approximately 40 degrees. B, hypokyphotic thoracic spine. C, Hyperkyphotic thoracic spine. Reproduced with permission from Joseph E. Muscolino. Artwork by Giovanni Rimasti. Figures B and C originally published in the massage therapy journal.

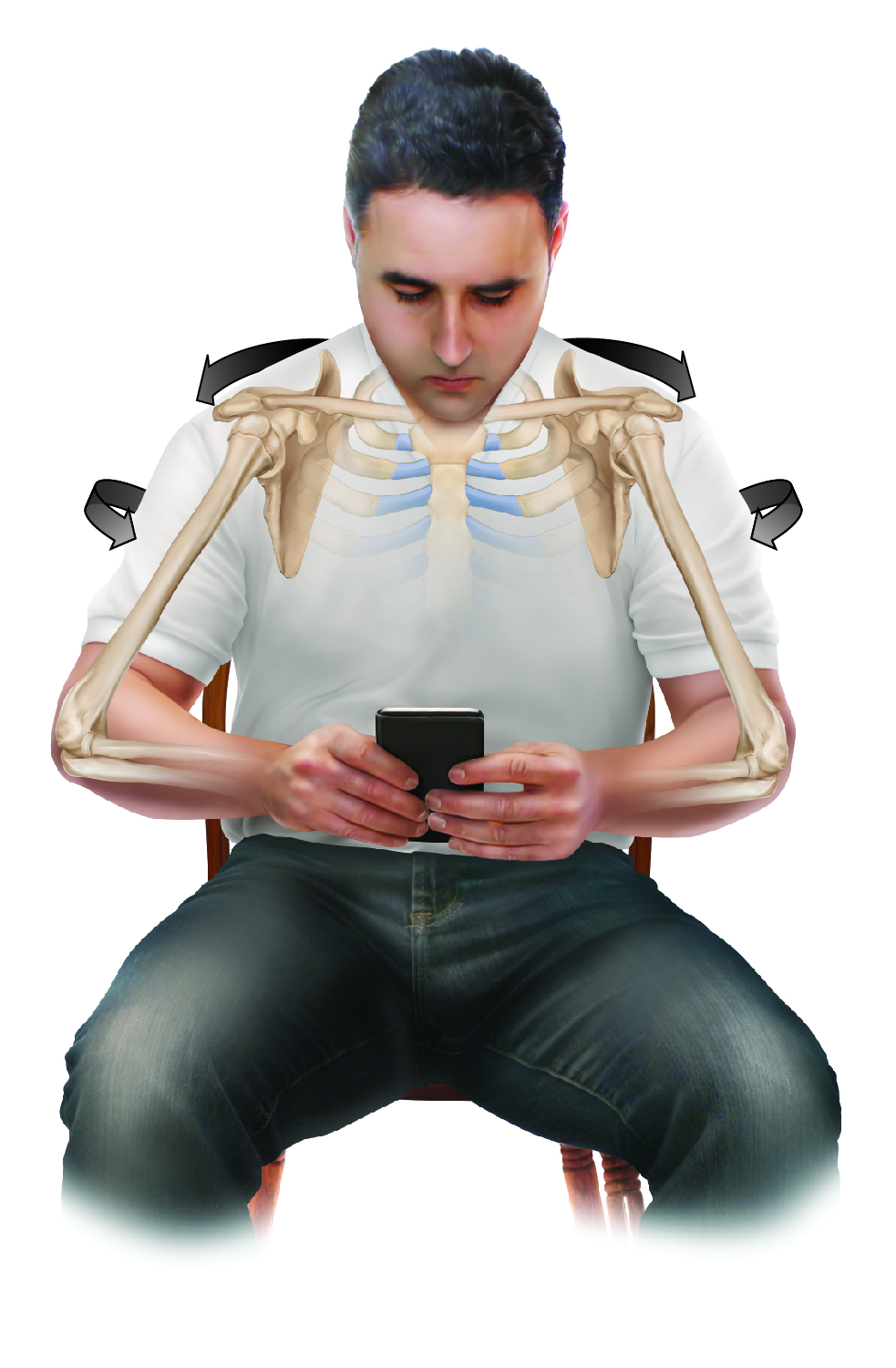

A kyphotic curve is effectively a curve of flexion. So it makes sense that assuming forward flexed postures on a regular basis would lead to a hyperkyphotic, in other words hyperflexed, rounded thoracic posture. And in our modern world, most everything that we do is down in front of us, whether it is tending to a baby, cleaning a counter, cutting vegetables, doing paperwork, or working with a laptop, tablet, or smart phone (Figure 2). Indeed, working down in front of our body is not new, but with the tremendous proliferation of digital devices, the number of hours that people spend hunched forward into flexion has grown exponentially. Indeed, it seems that hyperkyphosis of the thoracic spine is becoming more and more prevalent, and may now be the most common and problematic postural distortion pattern that manual and movement therapists encounter.

Figure 2. Working down in front of our body tends to promote a hyperflexed (hyperkyphotic) rounded thoracic spine. Reproduced with permission from Joseph E. Muscolino. Artwork by Giovanni Rimasti. Originally published in the massage therapy journal.

Like any postural distortion pattern, the longer we assume a rounded back posture, the more the soft tissues adapt to the distortional pattern. With a rounded thoracic spine, the anterior pectoral musculature ends up shortening and tightening and the posterior spinal extensor musculature ends up lengthening and tightens in response. Further, the anteriorly located fascial/ligamentous tissue shortens and becomes taut and the posterior fascial/ligamentous tissue lengthens and “weakens”, thereby losing the tautness/tone to oppose the forward flexion. As the fascial tissue weakens, this increases the burden on the extensor musculature, which becomes further overwhelmed and dysfunctional in its attempt to prevent the forward progression.

And as we move further into flexion, our center of weight moves anteriorly, increasing the leverage force of gravity, which furthers the force toward a forward flexed posture. Additionally, staying stuck in a rounded back posture also allows the buildup of fascial adhesions (often described as “fuzz” by educator Gil Hedley) that further resist the body from moving back into extension. And when extremely long standing, for years or decades, even the bones remodel. The anterior aspects of the vertebral bodies narrow in height in response to the increased weight-bearing compression force anteriorly. All these factors add up to a postural distortional pattern that, once set in motion, tends to become a vicious cycle that feeds upon itself, steadily and progressively worsening. So what begins as a seemingly innocuous voluntary forward posture that we pay little attention to, often transitions into a stubborn, rigid dysfunctional pattern in which we become stuck, that alters the health of the thoracic spine, and indeed, much of the rest of the upper body.

Upper Crossed Syndrome (UCS)

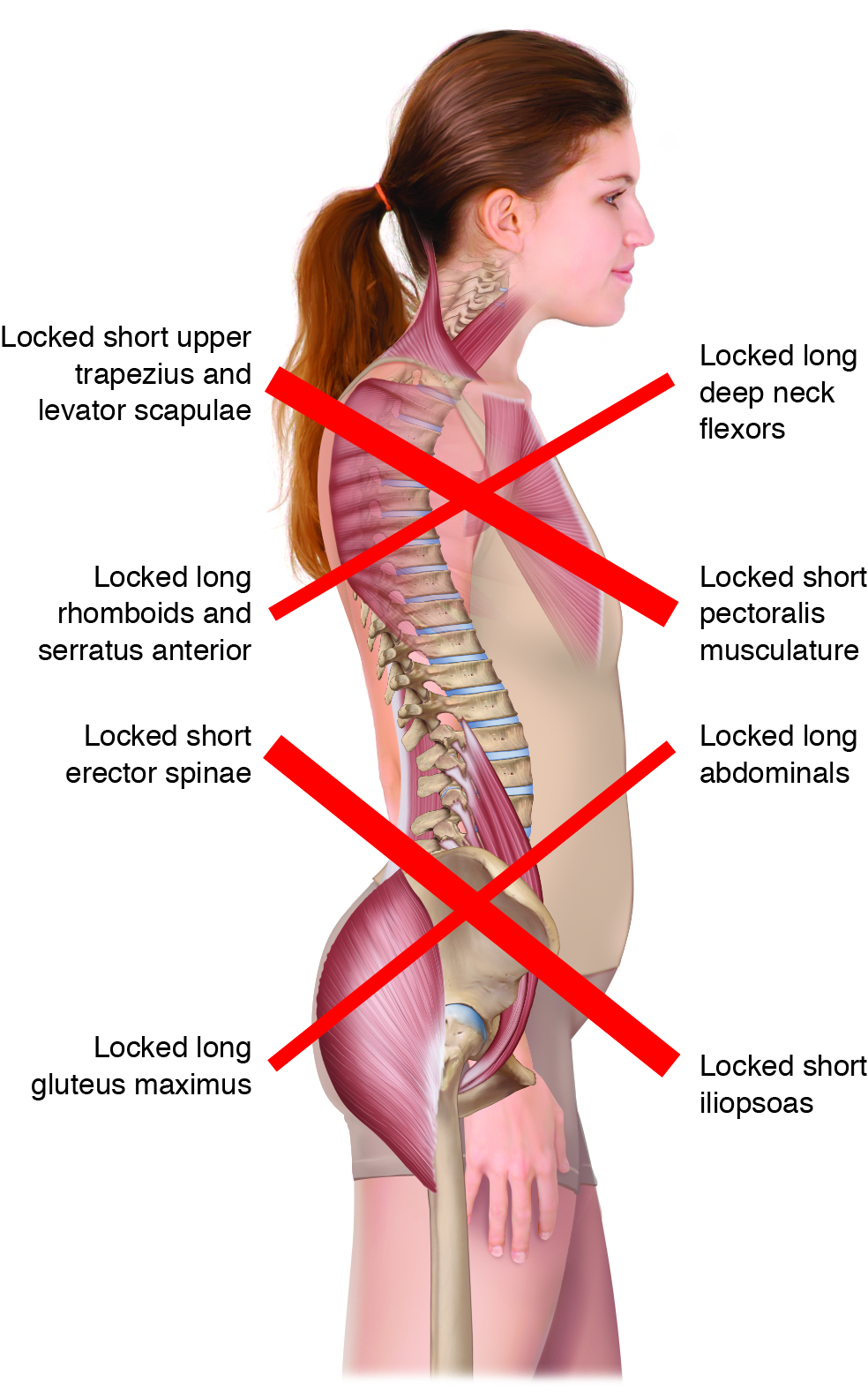

A rounded thoracic spine does not exist in isolation. Rather, it is usually part of a larger dysfunctional pattern that involves the neck, head, shoulder girdles, and arms. This larger pattern is often described as upper crossed syndrome (UCS) and is so named because a cross (X) can be placed across the upper body. One arm of the cross represents overly facilitated (“locked-short”) musculature; the other arm represents overly inhibited (“locked-long”) musculature. The effect of the imbalanced asymmetrical pulls of the musculature results in the characteristic UCS posture which involves hyperkyphosis of the thoracic spine, hypolordosis of the lower cervical spine, hyperlordosis of the upper cervical spine, forward head carriage, protraction of the shoulder girdles, and medial/internal rotation of the arms at the glenohumeral joints (Figure 3). Even though each of these postural distortions can be viewed as a separate entity, in reality each one tends to increase the dysfunction of the others. But the rounded back thoracic hyperkyphosis is most fundamentally the root cause of the UCS pattern.

Figure 3. Upper Crossed Syndrome. Reproduced with permission from Joseph E. Muscolino. Kinesiology: The Skeletal System and Muscle Function, 3ed. Artwork by Giovanni Rimasti.

Effect upon the Cervical Spine

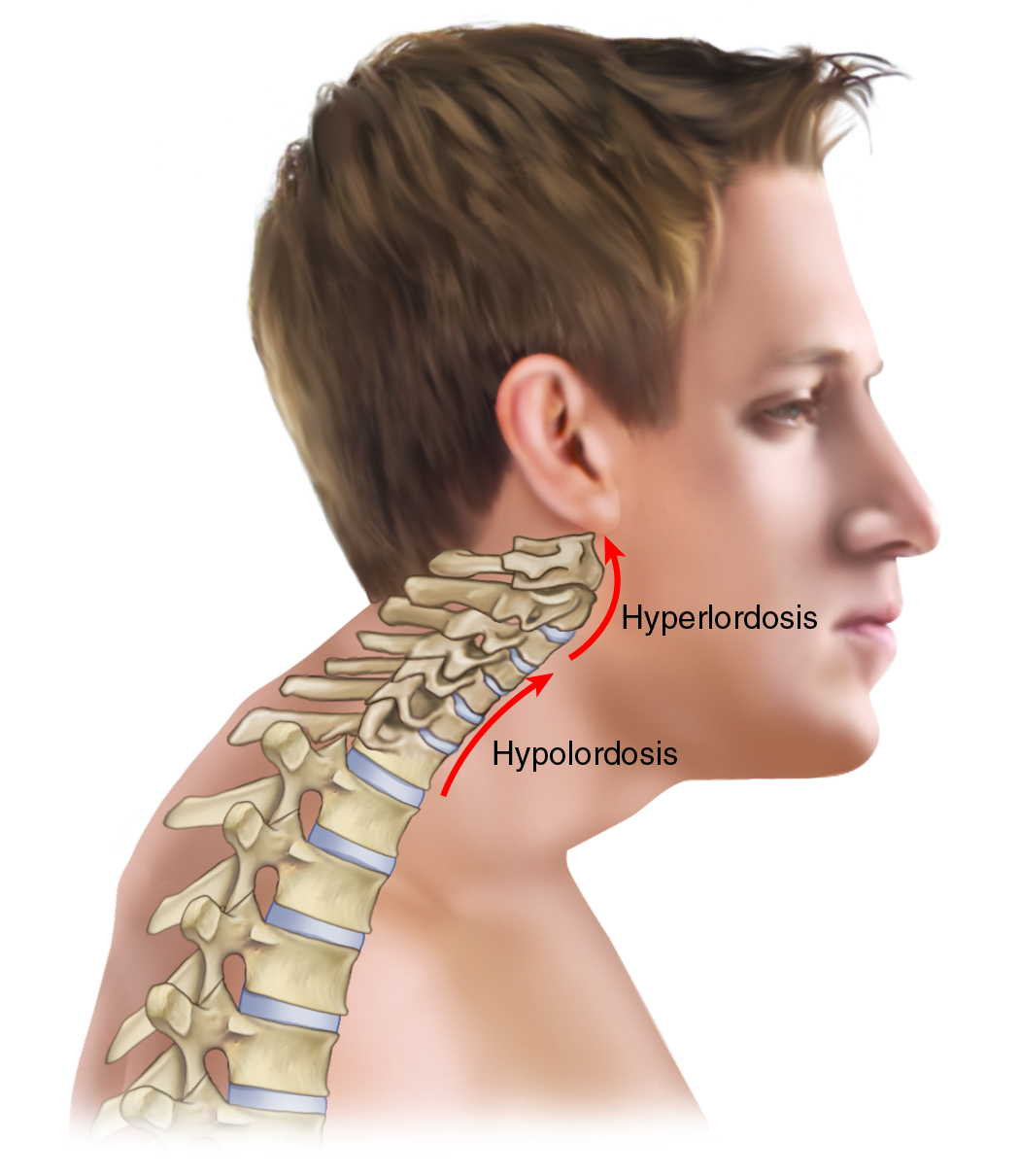

Once we flex the thoracic spine forward, the cervical spine must begin its posture on the superior aspect of the body of T1 that is now more vertically oriented. This projects the lower neck anteriorly, continuing the path of the upper thoracic spine, causing the lower cervical spine to be hypolordotic. As a necessary compensation, the upper cervical spine must become hyperlordotic to bring the eyes and inner ears lever for proprioception (Figure 4). These dysfunctional cervical postures alter the balance of weight bearing through the cervical spinal joints. Hypolordosis/flexion of the lower cervical spine increases weight bearing through the discs, increasing the likelihood of disc pathology. Hyperlordosis/extension of the upper cervical spine increases weight bearing through the facets, increasing the likelihood of facet irritation and degenerative osteoarthritic changes. These conditions, in turn, increase the likelihood of nerve compression in the intervertebral foramina.

Figure 4. Effect of a rounded thoracic spine on the posture of the neck and head. Note hypolordosis of the lower cervical spine, hyperlordosis of the upper cervical spine, and the forward head posture. Reproduced with permission from Joseph E. Muscolino. Artwork by Giovanni Rimasti.

Effect upon Forward Head Carriage

This altered cervical posture also results in a forward head carriage in which the center of weight of the head is located anterior to the trunk, over thin air (see Figure 4). This imbalanced posture requires the posterior soft tissues to work harder to keep the head from falling into flexion due to gravity, resulting in tighter posterior, extensor cervicocranial musculature, in other words spasmed neck muscles, likely causing neck pain, myofascial trigger point referral pain, and tension headaches.

Effect upon Shoulder Posture

Further, once the thoracic spine rounds forward, the shoulder girdles cannot maintain a posterior posture and therefore fall into protraction; and the arms follow suit by falling into medial/internal rotation (Figure 5). These upper extremity distortional postures often result in increased stress upon the muscles, resulting in tightness, pain, trigger point formation (along with referral of pain) and fascial adhesions. Further, a medially rotated humerus decreases abduction and flexion range of motion of the arm.

Figure 5. Rounded thoracic spine also leads to protracted scapulae and medially rotated humeri. Reproduced with permission from Joseph E. Muscolino. Artwork by Giovanni Rimasti.

To experience this, try abducting and/or flexing your arm with the arm first medially rotated. Then repeat the motion with the arm laterally rotated, and note the difference in range of motion. A medially rotated arm also increases the likelihood of shoulder impingement syndrome of the supraspinatus tendon and subacromial bursa (due to the approximation of the greater tubercle against the acromion process of the scapula above).

Effect upon Thoracic Outlet Syndrome

And if this were not enough, UCS also increases the likelihood of all three myofascial forms of thoracic outlet syndrome: pectoralis minor syndrome, costoclavicular syndrome, and anterior scalene syndrome. Pectoralis minor syndrome due to the locked-short pectoralis minor; costoclavicular syndrome due to the collapsed posture of the clavicle against the first rib; and anterior scalene syndrome due to the adaptive shortening of the scalene musculature.

Effect upon Breathing

UCS even inhibits our ability to breathe. This is easy to demonstrate. Flex your thoracic spine, protract your shoulder girdles, and medially rotate your arms, and try to take in a deep breath. It is difficult, correct? Now open up your body by extending your thoracic spine, retracting your shoulder girdles, and laterally rotating your arms, and take in a deep breath, and notice how much more easily you can breathe deeply. A flexed/protracted/medially rotated posture inhibits the ability of the thoracic cavity to expand, limiting our ability to intake air, thereby limiting our ability to oxygenate our blood, thereby limiting our ability to oxygenate all the tissues of our body.

Effect upon the Lumbar Spine

Effects of a rounded thoracic spine can even be felt inferiorly at the lumbar spine. By early middle age, a hyperkyphotic thoracic spine tends to become rigid, thereby limiting thoracic extension (as well as other ranges of motion). This places a greater demand on the lumbar spine to extend (Figure 6). This, in turn, results in increased compression force upon the lumbar facet joints, likely resulting in facet irritation, osteoarthritic degenerative changes (as well as possible foraminal encroachment and nerve impingement), joint dysfunction, and low back pain. Low back pain often then results in protective spasming of the nearby paraspinal extensor musculature, causing further joint dysfunction and low back pain. It is important to note that rigidity of the thoracic spine also impacts the cervical spine by similarly requiring the cervical spine to increase its range of motion to compensate for the rigid hypomobile thoracic spine. This places an increased stress upon the musculature and joints of the cervical spine, resulting in further pain and dysfunction there as well.

Figure 6. A rigid thoracic spine that is stuck in flexion places a greater demand on the lumber spine to extend when extension of the trunk is required. Reproduced with permission from Joseph E. Muscolino. Artwork by Giovanni Rimasti. Originally published in the massage therapy journal.

Lower Crossed Syndrome and the Thoracic Spine

Rounded back thoracic hyperkyphosis is often caused by and accompanied by a general rounding of the entire spine, including the lumbar region (see Figure 2). In these cases, the lumbar spine reverses its lordosis to become kyphotic and the thoracic spine continues this kyphosis, resulting in rounded posture of the entire thoracolumbar spine. However, even a hyperlordotic lumbar spine can result in a rounded hyperkyphotic thoracic posture. Lumbar hyperlordosis is a prominent feature of the postural distortional pattern that is known as lower crossed syndrome (LCS – see Figure 3). The hallmark feature of LCS is an excessively anteriorly tilted pelvis, which then results in a hyperlordotic (in other words, hyperextended) lumbar spine.

With LCS, because the lumbar spine is hyperextended, the center of weight of the trunk moves posteriorly. As a compensation to bring the trunk’s center of gravity back anteriorly, the thoracic spine must increase its flexion (kyphosis), thereby resulting in an excessively rounded thoracic spine (with all of its sequelae described in this article) (See accompanying Figure to the left – Reproduced with permission from Joseph E. Muscolino. Artwork by Giovanni Rimasti. Originally published in the massage therapy journal.)

With LCS, because the lumbar spine is hyperextended, the center of weight of the trunk moves posteriorly. As a compensation to bring the trunk’s center of gravity back anteriorly, the thoracic spine must increase its flexion (kyphosis), thereby resulting in an excessively rounded thoracic spine (with all of its sequelae described in this article) (See accompanying Figure to the left – Reproduced with permission from Joseph E. Muscolino. Artwork by Giovanni Rimasti. Originally published in the massage therapy journal.)

Assessment of Rounded Back

Assessment of a rounded back posture is straightforward. Simply observe the client from the side and assess the degree of thoracic kyphotic curve. This should be followed by palpation of the pectoral musculature, as well as palpation of the extensor musculature of the thoracic spine and retractor musculature of the shoulder girdle. Because chronic rounded back posture results in rigidity of the spine being stuck in flexion, gentle but firm motion palpation of the thoracic spinal joints should be done by challenging these joints to move into extension. This is accomplished by pressing (gently but firmly) directly midline on the thoracic spine of the prone client with the palm of the hand; placing the spinous processes in the intereminential groove (the groove between the thenar and hypothenar eminences) and feeling for the end-feel motion of the joints (Figure 7). A healthy joint has a firm but slightly elastic springy bounce at end-feel. If instead the end-feel is rigid, like hitting a concrete wall, then the joints being assessed are locked/hypomobile, likely due to intrinsic muscular spasming and fascial contractions. Because thoracic rigidity can cause dysfunctional compensations elsewhere, if thoracic hypomobility is identified, it is important to then assess for all of the possible related conditions.

Figure 7. Motion palpation assessment of the thoracic spine into extension. Reproduced with permission from Joseph E. Muscolino. Artwork by Giovanni Rimasti.

Treatment of Rounded Back

All effective clinical orthopedic manual therapy treatment should be directed at the fundamental underlying biomechanical and neurologic mechanisms that are causing the condition. With thoracic rounded back, the underlying mechanism is a chronic hyperflexed posture of the thoracic spine that then creates locked-short pectoral musculature anteriorly, locked-long thoracic musculature posteriorly, and hypomobile thoracic joints.

Treating Myofascial Tissue

Treatment of myofascial tissue should be directed toward loosening the anterior musculature, and loosening and strengthening the posterior musculature. Therefore the targets muscles to which treatment must be directed are the pectoral muscles anteriorly (pectoralis major, pectoralis minor, and the subclavius), and the posterior muscles of thoracic spinal extension (erector spinae and transversospinalis), shoulder girdle retraction (rhomboids and trapezius, especially middle trapezius), and humeral medial rotation (subscapularis, teres major, latissimus dorsi, anterior deltoid, and pectoralis major). There is no one magical soft tissue technique for loosening musculature, but a general approach is to use moist heat, followed by deep tissue massage, followed by stretching. If it is within your scope of practice, it is important to recommend to the client to strengthen the musculature of thoracic extension, shoulder girdle retraction, and humeral lateral rotation.

Treating the Thoracic Joints

All of this wonderful myofascial work will be ineffective if the client’s thoracic spinal joints are rigid and stuck in flexion. For these clients, it is imperative that Grade IV joint mobilization is performed, especially directed toward extension.* Grade IV joint mobilization involves repeated gentle but firm oscillations directed toward moving the joint into the ranges of motion that are decreased. These oscillations are usually repeated for approximately 15-30 seconds. For extension joint mobilization, the therapist simply directs the force from posterior to anterior midline on the spine of the prone client. In other words, it is performed in an identical manner to motion palpation assessment technique (see Figure 7). If this treatment technique is not within your scope, then the client should be referred to a soft-tissue oriented chiropractor or osteopath for adjunctive care. Note: Be aware that joint mobilization is contraindicated if the client has any hypermobility/instability of tissue locally where the treatment is being rendered (for example, osteoporosis/osteopenia).

* Grade IV joint mobilization is legal and ethical for most manual therapists. To be sure that this technique is within your scope, please check with your state/provincial licensing/certifying body. It should be emphasized that Grade IV joint mobilization does NOT involve a fast thrust.

Self-Care Recommendations

Home self-care consisting of hot shower (or other form of moist heat) followed by foam rolling or working with therapeutic balls for work into the myofascial tissue. Following moist heat application with stretching is also extremely valuable. One easy and excellent way to stretch the thoracic spine into extension is to use a gym ball (Figure 8). And strengthening exercises for spinal extension, shoulder girdle retraction, and glenohumeral lateral rotation should also be done on a regular basis.

Figure 8. Using a gym ball to stretch and open the thoracic spine into extension. Reproduced with permission from Joseph E. Muscolino. Artwork by Giovanni Rimasti.

Addressing Posture

Finally, given that the root cause of thoracic spinal hyperkyphosis is chronically assuming a rounded forward posture into flexion, it is imperative that the client begins to make lifestyle changes that eliminate these postures. For this reason, it is important to counsel the client about a wide range of postures including postures when using a desktop, laptop, tablet, smart phone, postures when writing or reading a book, postures when driving, and any other posture that might involve working down in front of their body.

Treating the Sequelae

Given that a rounded thoracic postural distortion pattern can spin off and create other secondary problems, it is important to not only assess for these secondary conditions but to also treat them as needed. Often, when the initial primary cause of a secondary condition is removed, the secondary condition resolves on its own without needed treatment. However, when the secondary condition is allowed to be present for a long period of time (months, years, or even decades), it becomes entrenched in the body. In these cases, it is usually not enough to simply remove the initial cause; rather, the secondary conditions must be individually targeted and treated.

Motivations for Treatment

The two most common signs/symptoms that direct a client toward seeking manual therapy treatment are pain and stiffness. Pain usually indicates that tissue damage is occurring, and is probably the primary reason that clients seek manual therapy. Stiffness (in other words, loss of range of motion), which usually indicates taut soft tissues is far less powerful toward compelling a client toward seeking care. Decreased range of motion is often ignored or not even noticed, especially when it occurs in small increments over long periods of time. This, unfortunately, is the circumstance with rounded back posture. Because the progressively greater thoracic kyphosis occurs so insidiously, often over months, years, or even decades, the client pays little or no attention to it. Even becoming self-aware of the distortional posture is not that noticeable to the client because looking in the mirror affords the client an anterior view, which does not show well the condition; a lateral view is usually needed to appreciate the extent of the rounded posture that is occurring.

Conclusion: The Thoracic Spine as Silent Saboteur

The major reason that rounded back posture does not motivate the client to seek care is that the ensuing rigidity of the thoracic spine rarely causes pain. As a result, by the time that the client notices a problem, it is usually years and decades chronic and now much more firmly entrenched. And by this point in time, it has set in motion the other postural distortional sequelae of the cervical spine, head, shoulder girdles, arms, and lumbar spine. Ironically, it is often the pain in these other regions that initially motivates the client to seek manual therapy care. At that point in time, while direct manual therapy is needed for these other regions of the body for immediate alleviation of their symptoms, manual therapy to the asymptomatic thoracic region is crucially important for long-term relief. For example, when a clients come in with neck pain, I often like to tell them that if they want their neck to feel better today, I will work the neck today; but if they want their neck to feel better six months from now, I need to work their thoracic spine. It is simply not possible for a neck to be functional and healthy if the thoracic spine is hyperkyphotic! The same concept often holds true for the shoulders or low back. For all these regions, the thoracic spine is truly a silent saboteur that must be considered and addressed when performing clinical orthopedic manual therapy care with our clients.

Note: This article has been slightly modified from the same-titled article that was originally published in massage and bodywork magazine in the july/august, 2016 issue.