Pathologic discs of the cervical spine are extremely common.

Although any pathologic disc is potentially serious, the degree of symptoms and functional impairment can vary tremendously. Some pathologic discs require immediate surgery, whereas others cause no problem and may be found, if at all, only incidentally when magnetic resonance imaging or a computed tomography scan is done for another reason.

Description of Pathologic Disc Conditions:

There are two major types of pathologic conditions of the intervertebral disc:

- Disc thinning

- Bulging or rupture of the fibers of the annulus fibrosus

Note: The commonly used lay term “slipped disc” does not really mean anything.

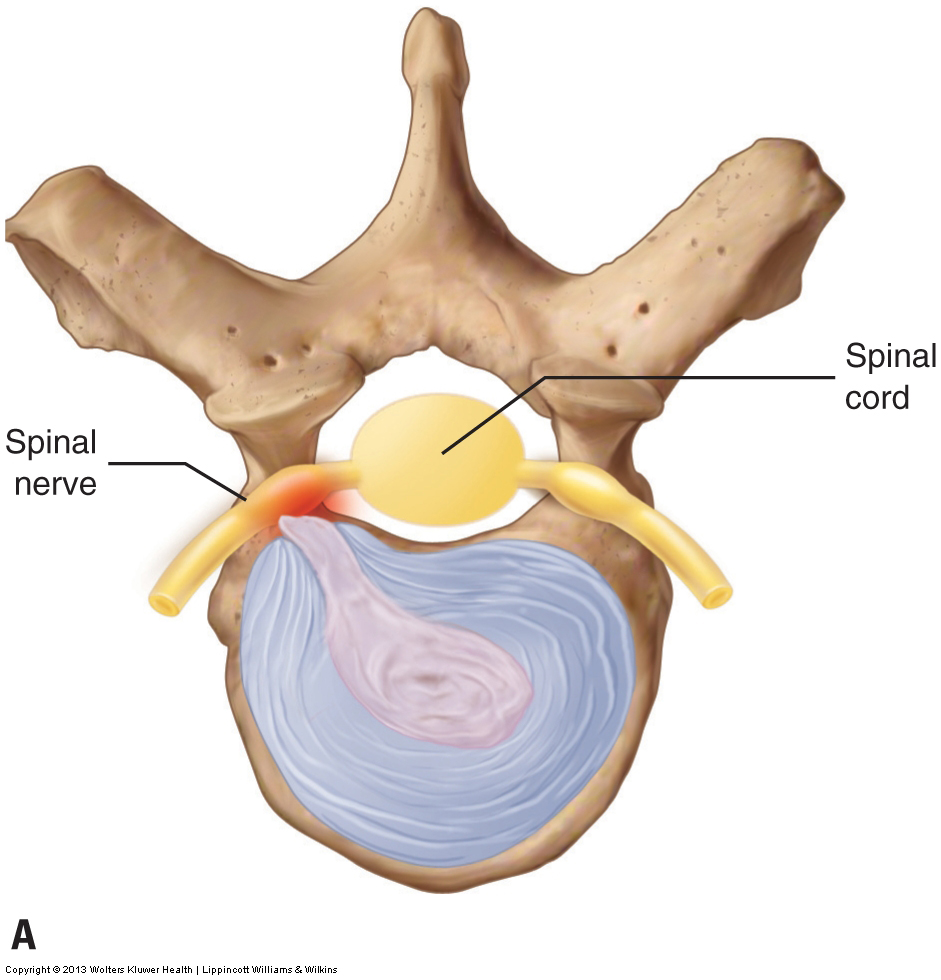

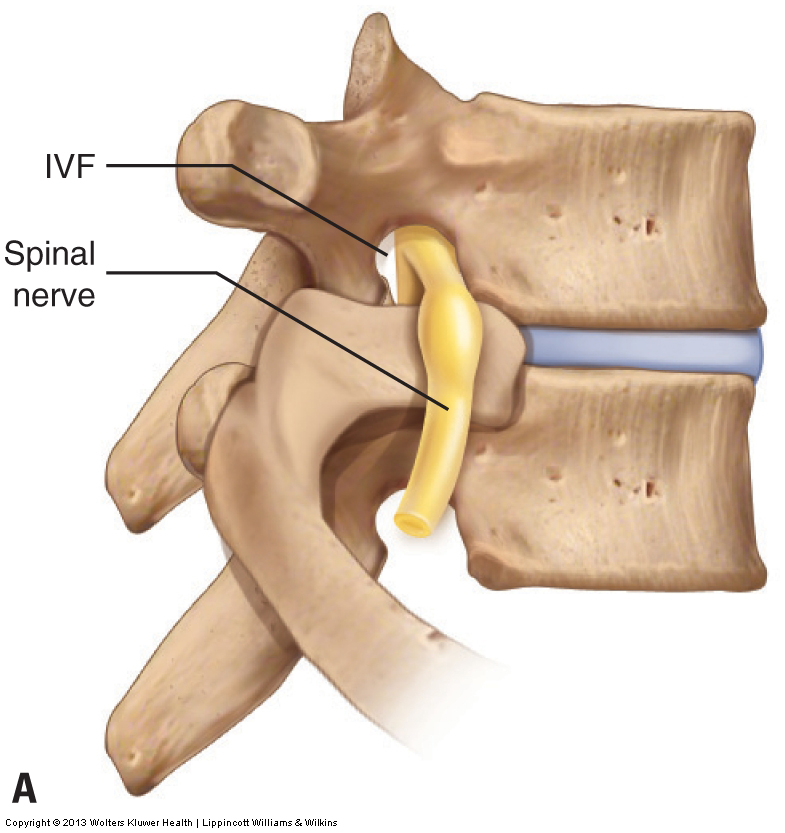

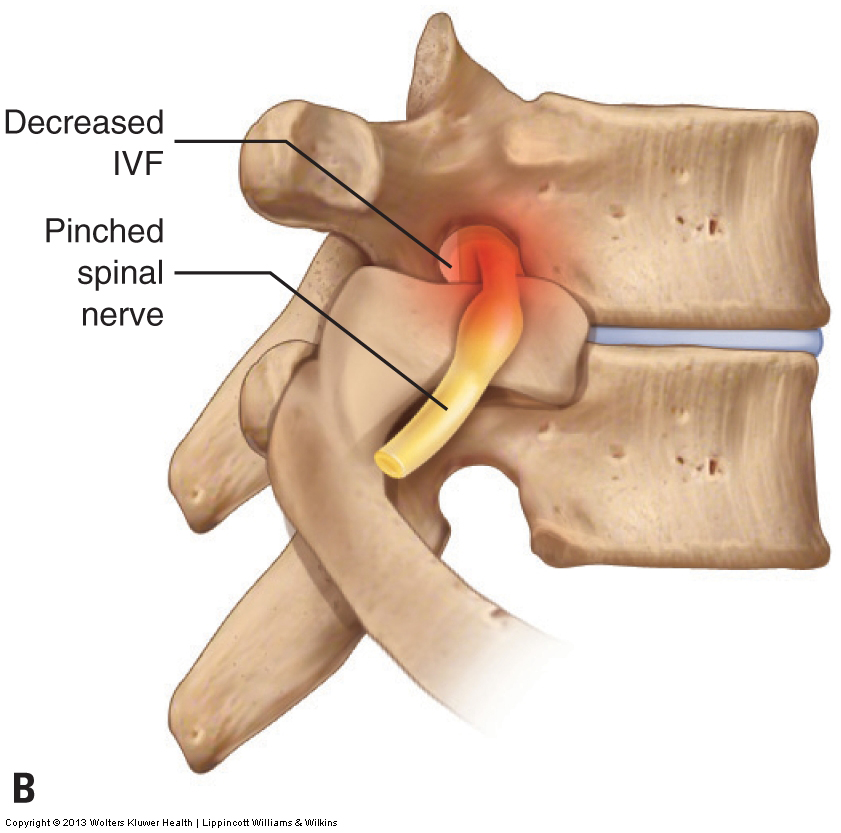

Disc thinning involves a decrease in the height of the disc. Given that the volume of the inner nucleus pulposus determines the height of the disc, disc thinning occurs as the nucleus pulposus gradually desiccates with age. This condition usually occurs when the client is middle-aged or older. The danger of disc thinning is that as the two adjacent vertebrae approach each other, there is a decrease in size of the intervertebral foramina at that level through which the spinal nerves pass (Fig. 12AB).

Figure 12. Disc height and the size of the intervertebral foramen (IVF). A, The disc is healthy and there is normal sized IVF. B, The disc has thinned, resulting in an IVF that decreased in size and impingement of the spinal nerve. (Note: The vertebrae shown are not cervical vertebrae, but are exemplary of typical vertebrae and their discs.)

Thus, if disc thinning becomes marked in degree, spinal nerve compression is possible. Because a spinal nerve carries both sensory and motor neurons, altered sensation can occur wherever the sensory neurons of that spinal nerve originated and/or altered motor function can occur wherever the motor neurons of that spinal nerve end. Sensory symptoms can include tingling, numbness, or pain; motor symptoms can include twitching, weakness, or flaccid paralysis of the musculature. Because the cervical spinal nerves innervate the upper extremity, these symptoms occur in the axillary region, arm, forearm, and/or hand. However, for most clients, disc thinning does not progress to the point that nerve compression with upper extremity referral occurs.

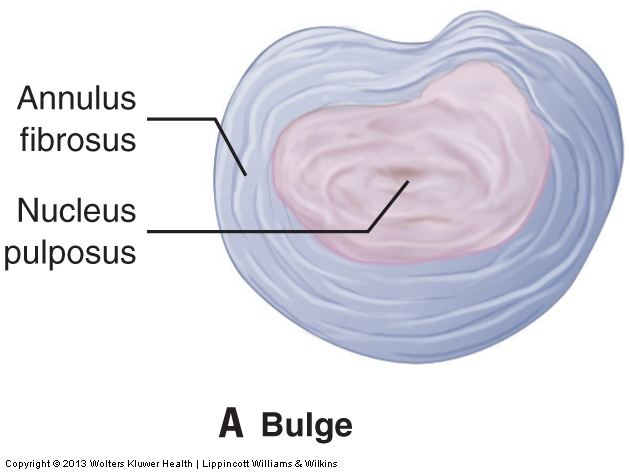

The other major type of pathologic disc condition is a weakening of the outer annulus fibrosus that leads to a bulging or rupture of its fibers. This condition has three major types/gradations of severity:

- Disc bulge

- Disc herniation (aka disc rupture or disc prolapse)

- Sequestered disc

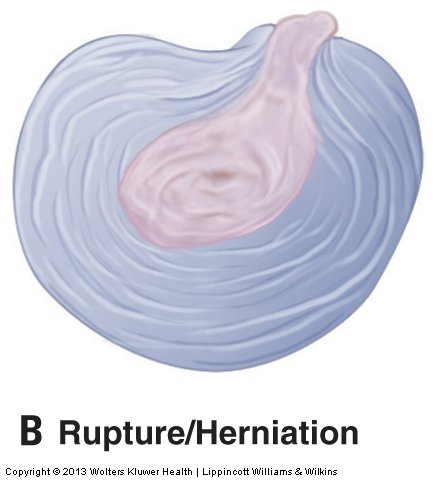

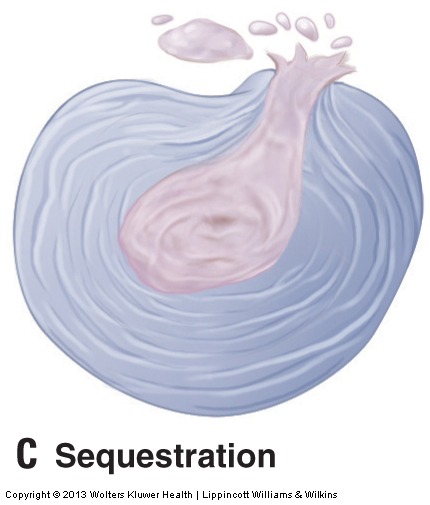

The mildest form is a disc bulge. In this condition, the annular fibers weaken and allow the nucleus pulposus to push against the annulus, causing it to bulge outward (Fig. 13A). A disc bulge is considered the mildest form because the annular fibers are still intact. A disc herniation (rupture) is considered the next degree of severity because the annular fibers have weakened to the point that the pressure of the nucleus pulposus causes them to rupture. In this case, the nucleus pulposus can actually extrude through the annulus and enter into the intervertebral foramen or spinal canal. A disc herniation is also known as a disc rupture or disc prolapse (Fig. 13B). The third and most severe form of this pathologic disc condition is the sequestered disc. A sequestered disc is a disc rupture in which a portion of the nucleus pulposus that extrudes through the annular fibers separates from the inner core of nucleus pulposus (Fig. 13C). It cannot rejoin the disc and is left to float within the intervertebral foramen or spinal canal.

Figure 13. Three forms of pathologic disc disease. A, Disc bulge. B, Disc herniation, aka ruptured disc, aka a disc prolapse. C, Sequestered disc, which is a disc herniation in which a piece of the nucleus pulposus that herniates through the annular fibers becomes separated from the main body of the nucleus pulposus.

The danger with disc bulges, herniations, and sequestrations is that the disc can push outward and compress the spinal nerve within the intervertebral foraminal space or the spinal cord within the space of the spinal canal at that level. Therefore, they are considered to be space-occupying lesions. With a bulging disc, the bulging annular fibers can compress the neural structures; with a ruptured or sequestered disc, the nucleus pulposus can create the compression.

The actual determinant of the severity of these conditions is the degree of nerve compression that occurs. For this reason, a large disc bulge can be much more problematic than a small disc rupture. Sequestered discs are usually the worst because the extruded fragment of nucleus pulposus remains in the intervertebral foramen or spinal canal and can continue to compress the spinal nerve or spinal cord, respectively.

Mechanism of Pathologic Disc Conditions

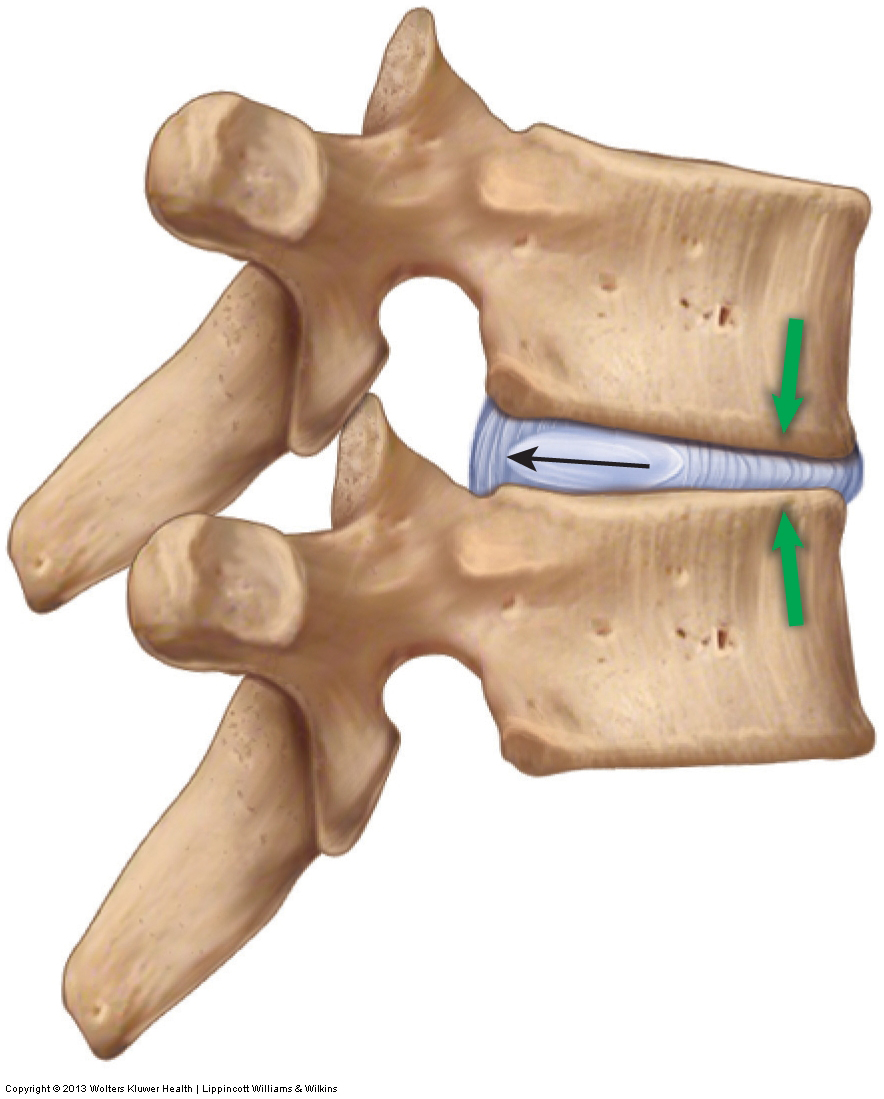

Annular bulges and ruptures occur as a result of forces that stress and weaken the annular fibers. These can be microtraumas or macrotraumas. Microtraumas are small physical stresses. One example is the everyday compression that results from supporting the weight of the head. Another example is holding a prolonged posture that stresses the disc, such as maintaining the neck in rotation due to a poorly placed computer monitor or flexing the neck to read a book held in the lap. Postures in which the head and neck are held forward in flexion are especially prevalent and contribute to disc problems because the position of flexion pushes the nucleus pulposus posteriorly, causing it continuously to push against and eventually weaken the posterior fibers of the annulus (Fig. 14). These microtraumas accrue over time and gradually weaken the annulus until the nucleus either causes it to bulge or ruptures through it.

Figure 14. Spinal flexion loads the anterior aspect of the disc which pushes the nucleus pulposus posteriorly against the taut posterior annular fibers. Excessive flexion postures tend to weaken and possibly eventually rupture the posterior/posterolateral annular fibers.

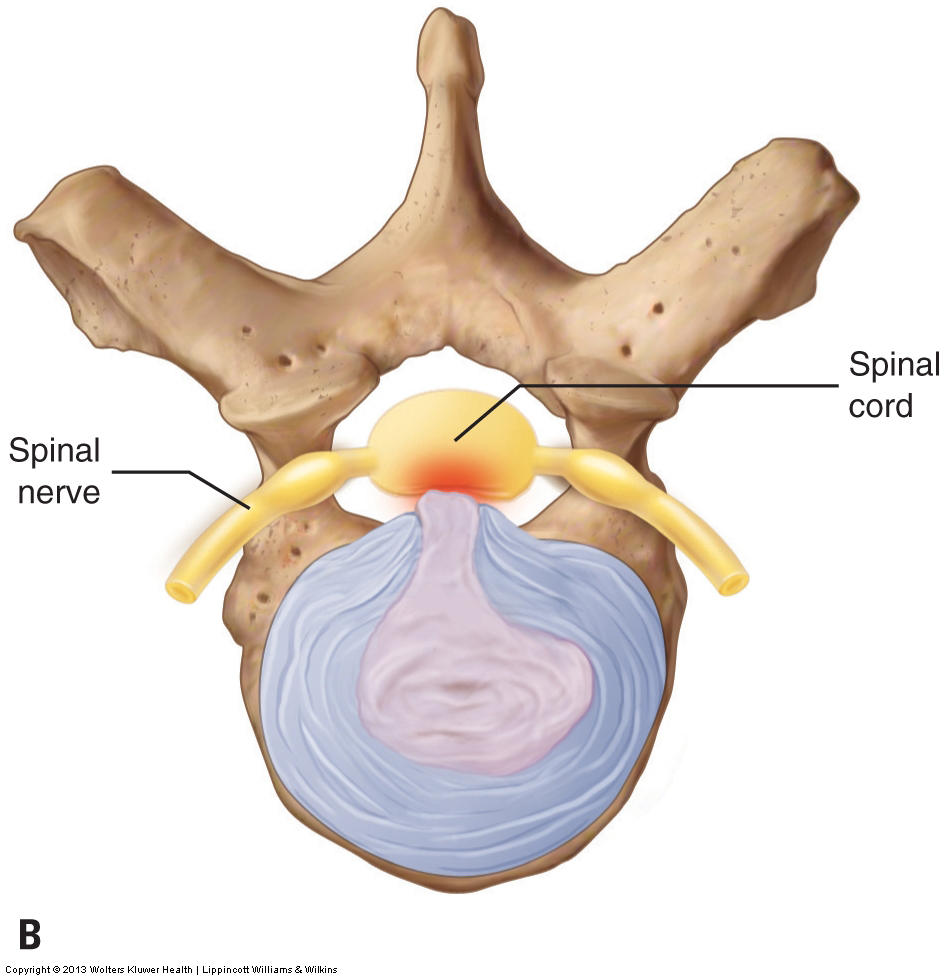

Macrotraumas such as severe whiplashes, traumatic sports injuries, or falls may also cause discs to bulge or rupture. Most often, a weakened disc from repeated postural microtraumas coupled with a somewhat traumatic event will cause the integrity of the fibers of the annulus fibrosus to fail, resulting in a bulge or rupture of its fibers. Most often, the annulus weakens and/or ruptures posterolaterally regardless of whether the pathologic disc occurs as a result of microtrauma or macrotrauma. The prevalence of flexion postures contributes to this problem because the postures cause the nucleus pulposus to push backward against the posterior annular fibers, gradually weakening them. However, because the posterior longitudinal ligament of the spine reinforces the annulus midline posteriorly (posteromedially), the effect of the physical stress of constant and recurring flexion postures usually manifests posterolaterally. Because the intervertebral foramina are located posterolaterally, most disc conditions result in compression of a spinal nerve in the intervertebral foramen on one side. If a disc were to bulge or rupture in the midline posteriorly, it would compress the spinal cord.

The symptoms of a disc bulge or rupture may refer to the upper extremity, occur in the neck alone, or both. Because most disc bulges/ruptures occur posterolaterally, compressing the spinal nerve in the intervertebral foramen, the result is unilateral sensory or motor symptoms that occur in the upper extremity on that side. Occasionally, a disc bulge or rupture may occur in the midline posteriorly. In such an instance, depending on which neurons of the cord are compressed, symptoms may be felt unilaterally or bilaterally and may be experienced in the upper extremity or even elsewhere in the body if the bulge or rupture is large (Fig. 15).

Figure 15. Disc herniation. A, Posterolateral herniation in which the spinal nerve is compressed in the IVF. B, Midline/central herniation in which the spinal cord itself is compressed in the spinal canal.

Symptoms may also be local if the small nerves in the disc area are compressed. When this occurs, pain occurs directly from this compression, and the neck muscles may protectively splint to stop movement that may further harm the disc. Unfortunately, the severity of the muscle spasming itself may cause pain, and the muscle splinting can increase the compression force on the discs, further aggravating the condition by increasing the size of the bulge or rupture. Note that when a disc condition is acute, inflammation can contribute to the neural compression, with the swelling itself producing symptoms. As the episode passes from the acute stage to the subacute and chronic stages, symptoms often decrease because swelling has diminished.

Click here for another blog post article that addresses the signs and symptoms of a pathologic disc of the spine.

Click here for another blog post article that discusses the causes of a pathologic disc of the spine.

Note: Tight Muscles and Disc Problems

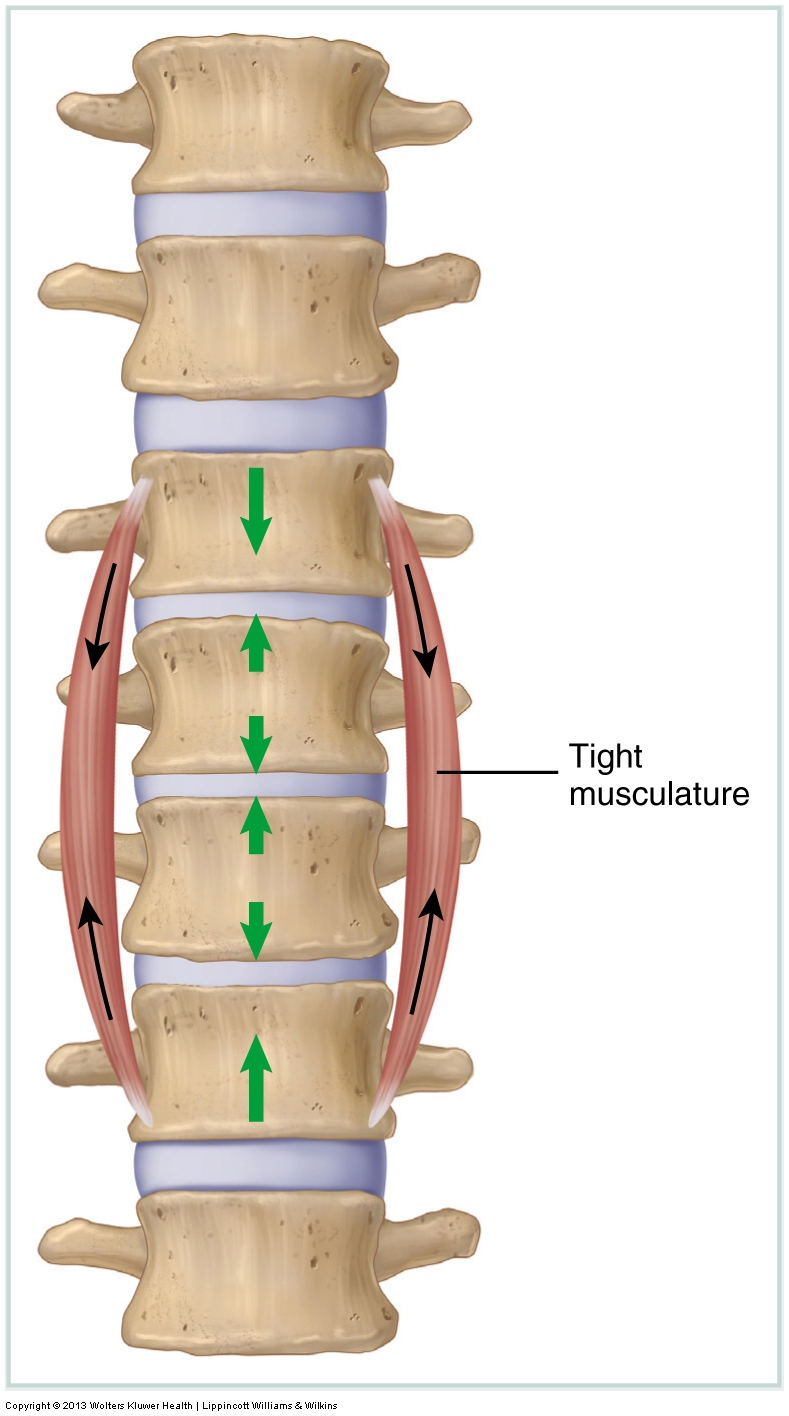

Perhaps the least appreciated but common microtrauma that contributes to spinal disc problems is tight muscles. When spinal muscles become tight, their attachments pull toward the center, drawing the vertebrae crossed by these muscles toward each other. This results in an increased compression on the discs (Fig. 16). Clients commonly have chronically tight neck muscles, which can contribute significantly to an eventual pathologic disc.

Figure 16. Tight baseline tone of musculature increases compression upon the joints that the musculature crosses. In the case of spinal joints, this increased compression increases load upon the discs, possibly causing or adding to disc disease.

Although local neck pain or spasming may occur, cervical pathologic discs often show no local symptoms at all and present with only upper extremity referral symptoms. If pain, tingling, numbness, or weaknesses are referred in the upper extremity, this should be a red flag that a disc problem may exist. However, this does not mean that all upper extremity referral symptoms come from a cervical disc bulge or rupture. Other conditions such as TOS, pronator teres syndrome, or even carpal tunnel syndrome may also refer symptoms to the upper extremity. Although a reasonably accurate assessment can be made with the appropriate orthopedic assessment procedures (see later blog post articles on treatment of neck conditions), if a cervical disc condition is suspected, the client should be referred immediately to a physician for a definitive diagnosis.

Note: Treatment Considerations in Brief for Pathologic Disc Conditions of the Neck

Massage can be extremely beneficial to help decrease muscular spasms associated with a pathologic disc. Stretching is also helpful, but the client’s neck should not be extended or laterally flexed to the side of a pathologic disc, or placed in any position that causes or increases referral of symptoms into the upper extremity. Furthermore, joint mobilization is contraindicated for any unstable/hypermobile tissue such as a bulging or herniated disc. Icing may help decrease some of the inflammation that accompanies a pathologic disc.

Of course, with any manual therapy treatment to the neck, there are always precautions and contraindications to consider given the number of sensitive structures present.

Note: All figures courtesy Joseph E. Muscolino. Originally published in Advanced Treatment Techniques for the Manual Therapist: Neck. 2013.

Note: This blog post article is the fifth in a series of 10 posts on

Common Musculoskeletal* Conditions of the Neck

The 10 Blog Posts in this Series are:

- Fascial Adhesions (and an introduction to musculoskeletal conditions of the neck)

- Hypertonic (tight) musculature

- Joint dysfunction

- Sprains and strains

- Pathologic disc conditions

- Osteoarthritis (OA)

- Thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS)

- Forward head posture

- Tension headaches

- Greater occipital neuralgia

(*perhaps a better term is “neuro-myo-fascio-skeletal”)