Self-care for the client/patient with De Quervain’s Syndrome:

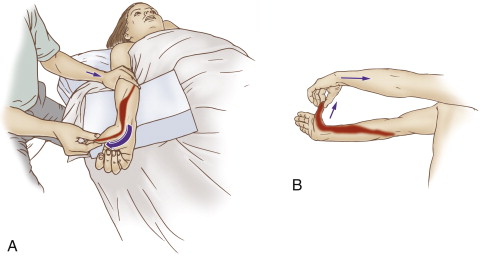

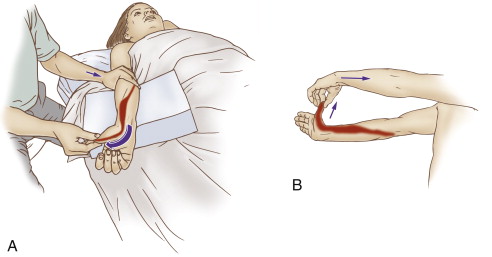

Gentle self-care (and therapist-assisted) stretch for De Quervain’s Syndrome. Permission: Joseph E. Muscolino. The Muscle and Bone Palpation Manual, with Trigger Points, Referral Zones, and Stretching, 2ed. (2016) Elsevier.

As stated earlier, self-care for De Quervain’s syndrome (De Quervain’s disease) is essential. Recommendation of frequent icing as well as gentle stretching as the condition permits is extremely important. The client/patient should be advised to avoid offending postures and activities of the thumb and wrist as much as possible; of course, with any condition that asks the client/patient to stop or minimize use of one hand, it is important that the client/patient does not overly stress the other hand by shifting all work to that side and overstressing and injuring the other hand as well. A night splint (brace) that holds the thumb and wrist in neutral position is also important so that the client/patient does not exacerbate the condition when sleeping at night.

Perhaps the most important self-care advice for De Quervain’s syndrome is to avoid as much as possible offending postures and activities of the thumb.

Medical approach to De Quervain’s Syndrome:

Because inflammation is a major factor with De Quervain’s syndrome, over the counter or prescription anti-inflammatory medication can be very effective toward resolving this condition. Cortisone injection is also another option that might be explored for more chronic or severe cases if manual therapy and oral medication is not successful.

Manual therapy case study for De Quervain’s Syndrome:

Grover is a 35-year-old pharmacist who tackled a home improvement job at his house. One part of the job required him to use a sanding block for a number of hours. After a few hours of sanding, Grover started to feel a strain in his right wrist as he was gripping the sanding block and pressing it against the wood, but he decided to push through and complete the job. When he was finished, his wrist was very sore, but he figured it would go away. The next morning, Grover noticed swelling on the thumb-side of his wrist. Instead of the pain going away, it gradually became worse over the next month until most every motion of his thumb precipitated the pain, and gripping objects became difficult. He finally decided to see a clinical orthopedic manual therapist.

The therapist performed active and passive ranges of motion of the thumb and of the hand at the wrist joint, as well as manual resistance to the thumb and wrist. Pain was elicited during the following motions: active and passive flexion and adduction of the thumb as well as ulnar deviation of the wrist joint, and manual resistance to abduction and extension of the thumb, as well as radial deviation of the wrist joint. Swelling was observed and palpatory tenderness was found near the styloid process of the radius. Finklestein’s test was positive and Grover indicated that it reproduced the characteristic pain that he has been feeling. Carpal bone motion palpation assessment was negative for joint dysfunction. The therapist also performed assessment tests for thoracic outlet syndrome and space-occupying lesions (nerve impingement in the intervertebral foramina) in the neck; these conditions tested negative.

Given the assessment of De Quervain’s syndrome, the therapist recommended two one-hour massages per week for three weeks, followed by one session per week for approximately the following seven weeks. Each session consisted of approximately 5-10 minutes of light work to the patient’s/client’s right forearm and hand to warm him up. This was followed by 10 minutes of moderate to deep work into the bellies of the abductor pollicis longus (APL) and extensor pollicis brevis (EPB) in the posterior forearm, and then five minutes of cross fiber work to the distal tendons of the same muscles, as then five minutes of pin and stretch to the APL and EPB. The therapist then iced Grover’s wrist on the radial side for five minutes. After this, the therapist spent the remaining time working the rest of Grover’s right upper quadrant and his left upper extremity. Grover was also given self-care instructions to ice a minimum of three times per day, to wear a splint when sleeping at night, and to minimize use of his right thumb.

At the end of three weeks, Grover’s felt approximately 25% better. Over the next two months, with continued orthopedic massage care and following the self-care instructions, Grover’s condition continued to gradually improve. It took approximately two months for his condition to subside to the point that he could comfortably use his thumb without pain for most tasks of everyday life. Grover then weaned his sessions down to once every two weeks for another two months, at which point in time, Grover no longer felt any pain with thumb use (except that he still experienced mild discomfort when performing Finklestein’s test). Grover then decreased his sessions to once per month for pro-active care.